The Kite Runner : not my kind of book

Also in today's blog

"an astonishing 1.25 million copies in paperback"

Tributes to Mark Barty-King

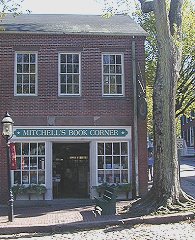

Mitchell's Book Corner, Nantucket

I sometimes test novels by opening them at random and reading five pages. If the book hasn't gripped me by then, it's probably a waste of time to start at the beginning.

Last week a friend lent me The Kite Runner with its appealing cover : a small boy with glossy black hair, brown skin and gym shoes peering round a corner, a picture sure to appeal to everyone who has or once had a son of that age. Also on the cover and inside it are extracts from nine laudatory reviews with 12 more on both sides of the back cover.

Last week a friend lent me The Kite Runner with its appealing cover : a small boy with glossy black hair, brown skin and gym shoes peering round a corner, a picture sure to appeal to everyone who has or once had a son of that age. Also on the cover and inside it are extracts from nine laudatory reviews with 12 more on both sides of the back cover.I opened Dr Khaled Hosseini's first book at p 145, the start of Chapter 13, and was immediately plunged into a party where Afghan music was playing. Five pages on a wedding was taking place at which, inside the momentary privacy of a veil flung over them, a young man tells his bride, for the first time, that he loves her. All this is happening in America. The bridegroom's father has spent $35,000 "nearly the balance of his life savings" on this wedding in a large Afghan banquet hall in Fremont.

If you read last Sunday's story about a real life wedding, you will know that I don't belong to the Let's Make A Splash brigade. So although I am interested in the customs of other countries, I'm repelled by conspicuous extravagance, the sort of people who go in for it being pretty much the same the world over, all equally obnoxious regardless of race or religion.

Feeling that the five pages I'd read couldn't be representative of a book so widely praised, I turned back to the beginning. Chapters 1 and 2 held my interest, but in Chapter 4 the central character, Amir, reveals a mean streak. Reading to his illiterate playmate, Hassan, he tells him that 'imbecile' means 'smart, intelligent'. Amir feels guilty about this later, but to the reader it is the first hint that he's not the kind of person you'd want beside you in a dangerous situation. On page 66 Amir watches Hassan being raped by a bully and does nothing to help him.

Maybe one shouldn't condemn a 12-year-old for cowardice, but it's hard to feel any liking for someone who runs away while their life-long friend is being tortured. Yes, Amir suffers great remorse through the rest of the novel, but remorse for despicable behaviour is not something the reader wants to share at interminable length, at least not this reader.

Later in the book, the bully, Assef, reappears and there is a horribly graphic scene in which he attacks and seriously injures Amir before having one of his own eyes shot out by a child with a sling-shot.

Two well-known women writers, Joanna Trollope and Isabel Allende, thought this book was excellent. Meghan O'Rourke's July 2005 review of the book at Slate points out its flaws and some of the reasons for its massive sales.

[Before I forget, on p 169 we read "I remembered when we used to lay forehead to forehead". How did that solecism get past the book's editor? The author is also prone to use 'like' in place of 'as if', which some people may not mind but I find jarring.]

"an astonishing 1.25 million copies in paperback"

Here's the opening of Ms O'Rourke's piece.

"Do I really have to read The Kite Runner? That was the question asked in the Slate offices this spring when the debut novel by Afghan-American Khaled Hosseini hit the top of the New York Times best-seller list. The novel seemed eminently worthy, after all-not only the first one written in English by an Afghan, but chock-full of "eye-opening information about the turmoil in modern-day Afghanistan," as one reader put it. The Kite Runner has sold an astonishing 1.25 million copies in paperback, driven by word-of-mouth at a moment when sales of fiction are reportedly at a low. Scores of municipalities selected it for their Community Reads programs, citing its "universal" themes. Laura Bush called it "really great." As the months have passed, America has only grown more passionate about its merits. So here's the mystery: Why have Americans, who traditionally avoid foreign literature like the plague, made The Kite Runner into a cultural touchstone? What version of life abroad is it that seems so palatable and approachable to us? Why The Kite Runner and not any of the other books about Afghanistan that have recently hit the shelves? The initial interest in the book clearly lay in the promise that it might deliver topical information in an accessible manner-humanizing the newspaper accounts of a place that suddenly became a U.S. preoccupation again after 9/11. This it does. Spanning nearly 30 years, The Kite Runner loosely fills in most of the relevant facts about Afghanistan's turbulent recent history-the 1978 civil war, the Soviet invasion, the rise of the Taliban opposition, the tension between the Pashtuns and the Shiite Hazara minority-and fleshes out the cartoonish picture many Americans have of Afghanistan as a culture of warlords and cave hideouts."

On Wednesday the expat book group to which I belong met for lunch in a small restaurant in the main square of Benissa. We were served by a tall, good-looking young woman who turned out to be also an expat, from Russia.

On Wednesday the expat book group to which I belong met for lunch in a small restaurant in the main square of Benissa. We were served by a tall, good-looking young woman who turned out to be also an expat, from Russia. I asked the five other group members, none of whom has read The Kite Runner, if they could empathise with someone who ran away when their best friend was in bad trouble. To my surprise they all said yes, they could.

That evening I put the question to Mr Bookworm who also, to my astonishment, said he thought Amir's behaviour was understandable if, by staying, he was likely to be beaten up and raped himself. But as we continued discussing the issue, Mr B conceded that, had it been one of his brothers who was in trouble, he wouldn't have left any of them in the lurch.

Perhaps this is the crux of the matter. Only children are more likely to have had a "best friend" and therefore see Amir's desertion of Hassan in the same light as people who have brothers or sisters would see it had Amir and Hasson been related rather than rich man's son and poor man's son thrown together by circumstances.

Mitchell's Book Corner, Nantucket

In preparation for our move to summer quarters later this month, I've been having a major sort-out in my workroom in Spain. Coming across a large envelope marked 'Nantucket', I found several pages of notes about the island's history and a hand-written thank you letter from a Nantucket bookseller. It was headed Mitchell's Book Corner, 54 Main Street, Nantucket

"June 13, 1983 Dear Miss Weale, I wanted to answer your nice letter and thank you right away for sending me Yesterday's Island. Naturally we'll be in touch with Harlequin (in a month or so) and order dozens. Then we'll do an ad on it. Should be great fun and good for the store.

Thank you for your complimentary reference to the bookshop. I'm now immortalised and very proud of it. Here's hoping you'll return to the island soon and see your book on our shelves. Best wishes and thanks again, Mimi Berman."

The story behind the letter is that, after spending some time exploring New England, Mr Bookworm and I ended our tour on Cape Cod and decided to catch the ferry to the island of Nantucket which sounded more our kind of place than the more fashionable island, Martha's Vineyard, where the Kennedy clan spent holidays.

We stayed at the Ship's Inn, built in 1831 by whaling captain Obed Starbuck. Nantucket was also the birthplace of Lucretia Mott, a famous abolitionist.

My notes include an extract from a book called Of Whales and Women by Frank B Gilbreth.

"No town of comparable size in America has had as much influence on the history of the world as Nantucket. Nantucket whalemen were the first to understand and map the Gulf Stream, and their finding revolutionised the traffic patterns between the Old World and the New. They were the first to explore both the Arctic and the Antarctic, and their discoveries are part of the basis of the American claim to Polar lands."

With its elegant houses, built with whaling fortunes, Nantucket was a delightful place to stay and within days of our arrival I had an idea for a book set there. The main characters in Yesterday's Island are Caroline Murray whose father was drowned off Nantucket when her mother was eight months pregnant. Consequently Caroline has never been to the island. The story opens with her godmother leaving her a half-share in a house there, the other legatee being an American, Hawkesworth Cabot Lowell the Third who turns out to be the master of a square-rigger, his being a cruise ship with sails in place of funnels.

Mark Barty-King

Over the years I've had the luck to meet many of the most interesting people in the UK publishing world. To my regret, I never met Mark Barty-King who, by all accounts, was the same kind of gentlemanly publisher as the legendary Boon brothers under whose aegis I started my career.

Over the years I've had the luck to meet many of the most interesting people in the UK publishing world. To my regret, I never met Mark Barty-King who, by all accounts, was the same kind of gentlemanly publisher as the legendary Boon brothers under whose aegis I started my career. Other tributes to him can be read here and

here

"Against the apparent modern trend, the publisher Mark Barty-King, who has died aged 68, believed that "the author is the most important person on the block". He understood the importance of personal relationships. His authors were often surprised to find that the receptionist knew who they were, that their books had been widely read throughout the company and that high hopes were not confined to their editor. Staff were encouraged to spot talent and given the chance to move from sales or marketing to editorial - and to try something new."